South Pole Diary - Jan/Feb 2004 -

Michael Ashley

Now

with illustrations and video clips

18th of January 2004 - Introduction

This is my fourth trip to the South Pole, and three years since my most

recent one, so I am looking forward to returning and seeing what has

changed. The University of New South Wales (UNSW) long-running and

highly successful AASTO experiment was completed at the end of last

year, and we are now embarking on a new experiment in collaboration with

Doug Caldwell, Kevin Martin and their colleagues at NASA's SETI

Institute. Here is Doug's

on-line diary, for a different viewpoint of the events in this diary.

The purpose of the experiment is to search for extra-solar planets,

i.e., planets around stars other than the sun. We are doing this using a

new telescope that is able to simultaneously observe thousands of stars

and monitor them for the small changes in brightness that occur when a

planet, by chance, happens to pass in front of the star. This has been

likened in difficulty to trying to detect an insect flying across the

headlights of a car 5km away.

It turns out that the South Pole has a number of advantages for this

sort of experiment, not least of which is that the stars never set, so

that you can monitor the same stars continuously. This is very

desirable, since a planetary transit may only last for a few hours,

which may be during daytime at a normal observatory. At the South Pole

the nighttime lasts six months.

I am traveling with Mark Jarnyk from Mount Stromlo Observatory. Mark is

a software expert who will be recommissioning the Gmount - a precision,

low-power, telescope mounting platform built at Mount Stromlo. In

preparation for our visit, Jessica Dempsey, a UNSW PhD student, is just

completing a two-week visit to the Pole during which she successfully

supervised the move of the AASTO to a new location about a kilometre

away from its previous location, but still just a few hundred metres

from the actual South Pole (we're talking -90S here).

In order to get to the South Pole I must first fly to Christchurch, New

Zealand, where I was met by a very helpful representative of Raytheon

Polar Services, the company that has been contracted by the US National

Science Foundation (NSF) to provide logistical support in Antarctica.

Within minutes of arrival I was whisked away on a shuttle bus to the

Windsor Private Hotel, an excellent little bed-and-breakfast

establishment in the heart of Christchurch, and a favourite amongst

modern Antarctic explorers.

It turns out that Christchurch is in the midst of holding the World

Busking Championships, and there are numerous jugglers, unicycle riders,

stand-up comedians, etc, around the city.

19th of January 2004 - Extreme Cold Weather clothing fit-out

At 1 p.m. we turned up at the Clothing Distribution Centre (CDC), near

Christchurch airport, to be fitted out with our Extreme Cold Weather

(ECW) clothing for the trip south. ECW consists of an amazing assortment

of gloves, balaclavas, parkas, goggles, rubber-insulated boots ("bunny

boots"), and intriguing items such as "expedition underdrawers" (suffice

to say that if you wore these in Sydney you would probably spontaneously

combust). Issuing of ECW is an extremely efficient process, and within

an hour we had tried on all the clothing and repacked it into the flight

bags for the flight to Antarctica.

We learn that we are scheduled to be at the airport tomorrow at 5:30

a.m. to check in for our 8 a.m. flight south to McMurdo. There are only

16 passengers on the flight, so we can expect to be jammed in with lots

of cargo.

We retire early to get some sleep before the flight. For some reason,

scores of late-night revelers seem to pass the time shouting to each

other for hours on the street outside my bedroom window. Christchurch on

a Monday night? All I can think of is that the buskers are having

a night on the town after performing all weekend.

20th of January 2004 - arrival at McMurdo, Antarctica

We awake at 4:30 a.m. to catch the shuttle to the airport at 5. Once at

the Clothing Distribution Centre we clamber into our ECW gear and

prepare for the briefing at 6:15. A customs official and his dog make

several passes over all of our luggage to make sure that we aren't

taking any drugs or other prohibited substances.

The safety briefing from the Loadmaster is somewhat more involved than

the usual airline version. For example, the oxygen masks don't just drop

from the ceiling, they require you to pull on a tab to break a seal that

releases them. You do this when you notice the airplane suddenly fills

with condensation and your colleagues pass out. There are also emergency

oxygen hoods which you pull over your head, and it is important to have

the chemical canister pointing in the right direction before you

activate it by pulling on various coloured tabs. The emergency exit

doors are also rather complicated, involving turning handles, lifting

levers, and pulling hatches aside, and if we need to exit via the roof

there are rope ladders to deploy, life vests to put on, and rubber rafts

to get into by climbing up a series of webbing ladders. The roof exit

appears to be about 0.5m on a side (far too small for our bulky

jackets), and is buried amidst an array of hydraulic pipes and

wires. We also receive instruction on how to prepare for being winched

out of the ocean by a helicopter. Let's hope that none of this will be

necessary. The Loadmaster was sounding very earnest though...

Spot the emegency exit in this photo... (actually there isn't one in

this particular picture, but it is typical of the inside of a C141).

I have interspersed this diary with movies (WMV format, which is

readily playable using Microsoft Media Player) and still images. The

movies are highly compressed, in order to be playable over a dial-up

connect. Here is the first movie, it shows part of the briefing at Christchurch before boarding

the airplane.

At the briefing I was surprised to find Jules Harnett, an Australian

astronomer, who is going to winterover at South Pole to help run the

AST/RO sub-millimetre telescope. Jules joins a long list of Australians

who have wintered at the Pole in various capacities.

We hear that our flight-time is 5 hours 15 minutes, which means that we

will be traveling in a C141 Starlifter, which is faster, quieter, but

not necessarily more comfortable than the usual LC130 Hercules. It's a

quick bus trip to the C141, where we grab in-flight lunches, and are

bundled into our spartan webbing seats.

The only windows in the C141 are towards the rear of the aircraft, and

we were strictly prohibited by the Loadmaster from clambering over the

cargo to take a look. Similarly, we were not allowed in the cockpit.

These were disappointments, since on previous trips I have been able to

observe the steadily increasing number of icebergs as we approach the

great frozen continent of Antarctica.

One of the passengers does try to sneak a look, but the Loadmaster sees

him and shouts "hoy!!" - it must have taken enormous lung-power for him

to be heard above the deafening noise of the engines, and through our

earplugs.

About an hour into the trip I notice that my feet were feeling a bit

numb, and then remembered that I had forgotten to depressurize my boots

before takeoff (the "bunny boots" are air-insulated, and they have a

value on the side which is supposed to be opened during flight, else the

boot expands and compresses your feet).

If the plane did have to ditch in the Southern Ocean, then you would

probably float suspended upside down from your bunny boots, until they

filled with water, at which point you would sink.

But let's not dwell on these topics.

A little over 5 hours later we touch down on the Pegagus blue-ice

runway, perhaps 20km from McMurdo itself, and built on the permanent

ice-sheet covering the Ross Sea. Here we are preparing to

disembark from the C141, and here are

our first steps off the aircraft on to Antarctica.

A large vehicle takes us the 20km into the town of McMurdo, or Mactown

as it is known by its inhabitants. It is the main American logistic hub

for Antarctica with a summer population of over 1000 people, and just

6km or so from Scott Base, the New Zealand station. First stop in

McMurdo is the NSF building, or "Chalet", where we receive a briefing. We discover that

we have the option of going to the Pole a day early, i.e., tomorrow, so

we take it. After the briefing, we are given our room assignments,

collect our checked baggage from the MCC (Movement Control Center), have

dinner, and then at 7pm lug our bags back to the MCC for another

weigh-in. This process is called "bag-drag", which is an apt

description. The MCC is perched on the top of a hill, so it can be quite

a struggle to get to it, with bags, while wearing full ECW gear.

After this process is over, I visited the Crary Lab and used the

telescope they have in the library to search for penguins. There were

lots of Weddell seals lying around doing nothing, but no penguins. But

then, out of the corner of my eye, I noticed a plume of water in the

distance. Sure enough, there was a pod of perhaps 20-30 orcas

(whale-like creatures with a fin like a dolphin) frolicking in the open

sea where the icebreaker had recently made a cutting. I watched for

half-an-hour while the orcas leapt out of the sea, spouted, and

generally had a good time. No penguins though.

Meanwhile, Mark had acquired the key to Scott Hut, so we traipsed down

there and had a good look around.

Scott's Hut was built in 1902, and was used by several expeditions up

until 1913. It is in excellent condition, and provided a welcome respite

from the wind outside.

There is still perhaps 50kg of original seal meat from 1913 remaining

in the hut. Here is an example of some on the veranda.

And there were lots of cases of "Special Dog Biscuits" and "Special

Sledging Rations". When I first visited McMurdo in 1995, the food was so

appalling that John Storey and I contemplated raiding Scott's Hut, or

perhaps using a GPS to locate Scott's last food cache. Fortunately, the

food at McMurdo is now excellent, and I hear that during wintertime it

is even better.

Walking back to McMurdo from Scott's Hut, I took a photo of the coast

guard icebreaker.

21st of January 2004 - the South Pole

At 6am, its rise and shine for breakfast and the trip to South Pole. No

hitches, and we are in the air in a LC130 Hercules aircraft by 8:30am.

the "L" in "LC130" means that this is a specially modified aircraft that

can land on either skis or wheels.

This time our Loadmaster was much more relaxed, and we were allowed all

over the aircraft and cockpit.

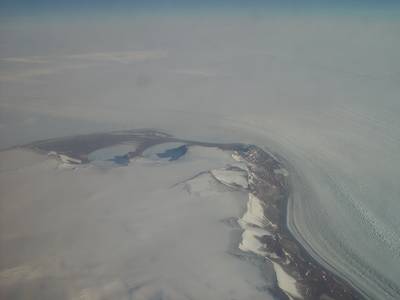

There were some spectacular views as we passed over the Trans-antarctic

Mountain range. The snow terrain was constantly changing: from crevasse

fields, to bare rock mountains, to smooth snow, pressure ridges, the

variety was amazing.

2h 45m after leaving McMurdo we arrived at the South Pole

(coincidentally, a British woman, Fiona Thornewill, had just covered

roughly the same distance by skis to the South Pole, in 42 days). It was

moderately warm for the Pole, -23C. The combination of the temperature,

the altitude (almost 3km), and the roar from the Hercules engines, all

make the experience of stepping onto the

ice an unusual one. We were whisked away in a van to the new South

Pole Station a few hundred metres away, where we discovered an

extraordinarily well-constructed modern building with superb facilities.

This is a huge improvement over the old South Pole Dome, where the

Galley was inside a small dark windowless room. In the new station the

Galley (or "Dining Facility" as it is now known) is some 15m off the

ice, and has panoramic views over the Antarctic plateau.

Not all functions have been transferred to the new building, so it is

still necessary to walk back and forth to the Dome - which entails

climbing 93 steps, which is no mean feat at the altitude of the Pole.

Speaking of altitude, I succumb to a moderately bad case of altitude

sickness, which starts with a severe headache after a few hours, then

vomiting. Fortunately I was able to get to the medical centre (in the

Dome) and the wonderful staff of dedicated people there took care of me

- oxygen, 2litres of IV solution, anti-nausea drugs, and pain

relief. Within a couple of hours I was feeling much better, and am 100%

as I write this 30 hours later. The doctor also provided me with an

oxygen concentrator machine for the night - this works by filtering out

the nitrogen in the air by some cunning process, leaving an enriched

supply of oxygen. The extra oxygen also help give you a good night's

sleep - whereas normally at this altitude I feel like I have been awake

all night (even though I must have dozed off).

Mark and I discover that we are sharing room A1-201, which is one of

the nicest on the station, being in the new building, within 30m of the

Dining Facility, and with two external windows looking down on the Dome.

Our beds have buttons on them to "Call nurse", and I later discover that

the room is used for overflow patients from the medical center - let's

hope that few people get sick. We also have individual desks, cupboards,

internet access, its a huge improvement from the canvas Jamesways that I

have previous been allocated.

22nd of January - first day of work

By lunchtime I had recovered enough to begin helping Mark, and Doug and

Kevin (who both arrived a few days earlier) out at our Weatherhaven tent

in the Dark Sector. The Dark Sector is the region of the Pole devoted to

astronomy, and is about a 1km walk from the new building. We are

assembling the telescope, mount, and control electronics, in the

Weatherhaven for final testing and balancing before moving everything to

its new location on top of the Gtower.

We have a productive day, and at 8pm hear a talk by Fiona Thornewill

(the woman I mentioned earlier who skied to the Pole in 42 days, which

shaved two days off the previous record). She did the trip by herself,

unsupported (i.e., no food drops or caches). She trained for 6 months by

pulling a truck tire for 2-3 hours a day, 6 days a week. Her problems

along the way included the failure of her Iridium phone (so no contact

with the outside world), failure of her main GPS (fortunately she had a

backup, but it used different batteries, which she didn't have an

abundance of), and intermittent failure of her fuel stoves. Her sledge

weighed 150kg when she started the trip. She is currently camped in a

small tent about 200m away from my luxury accommodation.

23rd of January - cable laying, Gmount problems

Doug and Kevin were eager to begin installing their equipment on the

Gtower today, which necessitates the laying of 10 bundles of cables from

the AASTO to the Gtower. This is no mean feat - their cables are about

30m long and are quite heavy, and have to be threaded through a conduit

in a trench in the snow.

The outside temperature is -26C (relatively warm for the Pole at this

time of year), but a brisk wind puts the windchill temperature (i.e.,

the equivalent temperature with no wind) at -48C. We work most of the

day at this problem, but don't complete it.

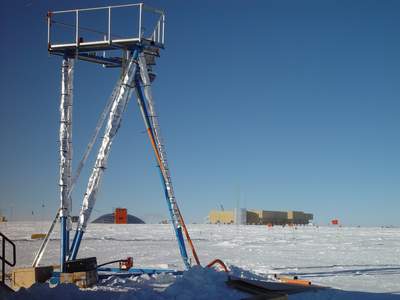

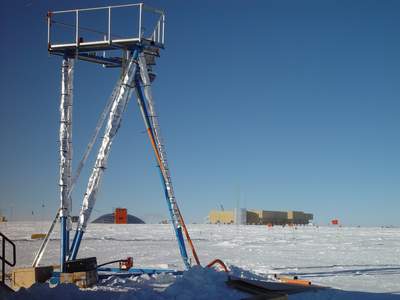

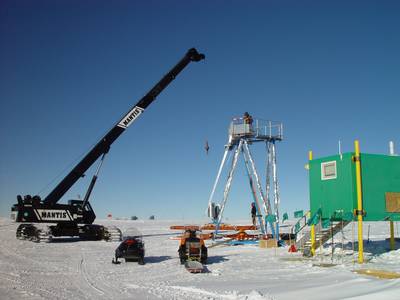

Here is an image of the Gtower, with the Dome visible underneath it,

and the new station building to the right. The silver cylinder in front

of the new building is the "Beer Can", and contains the infamous 93

steps you have to climb. People who have been here for a couple of weeks

can leap up the stairs two at a time, but newcomers find it quite

exhausting. It takes two weeks for the body to adapt to the altitude and

produce enough red blood cells to carry the needed oxygen.

In other news, Mark has discovered a potentially serious problem with

the Gmount - it appears as though both axis servo cards are

non-functional. While we have spares, we would like to understand what

caused the failure before trying them.

I installed a data processing computer in the ARO building (150m from

the AASTO) - this computer has 1.6TB of disk space (a lot!) and will be

used to analyse the images from the planet search experiment during the

year. The computer was put together by Melinda Taylor at UNSW, who did

an excellent job.

At lunch time I met two highly animated geologists who thrust a plastic

bag containing a 1kg rock into my hand and told me it was a meteorite

they had just collected at the LaPaz ice field some 300km from the Pole.

The two men were in a party of 8 who have returned to Pole after 40 days

in the field collecting meteorites. Of the couple of hundred they found,

they suspect one or two may be martian or lunar in origin. The

particular rock they let me hold was formed 4.5 billion years old, and

had probably struck the ice sometime in the last 100,000 years. The

rocks are naturally swept to the surface at LaPaz, due to the nature of

the ice movements and underlying rocks. The geologists just have to

ski-doo around and pick them up (I'm sure there is more to it than

that...).

24th of January 2004 - ski-doo ride from hell, more cable laying

After breakfast I trudged the 1km or so out to the Weatherhaven tent to

inspect the Gmount schematics to see if I could shed any light on the

servo problem. I then trudged another 1km over to the AASTO to help with

operations there. At this altitude, and with a stiff wind, it is quite

energetic just walking around - it puts into perspective the 30km or so

per day that Fiona Thornewill managed with a 150kg sled.

We discover that one of our two Uninterruptible Power Supplies (UPS)

has failed, fortunately there is a spare back at the MAPO building (near

the Weatherhaven), so I volunteer to help Kevin with moving it over.

Kevin has been checked-out to use the ski-doo, and is an experienced

driver with 2km under his belt (heavy irony here). We call past COMS in

the Dome to pick up the key, and then walk through the fuel arches to

find the ski-doo. After a few attempts it starts, but refuses to travel

up the slight incline on which it was parked at more than a few cm a

second. Then Kevin guns it, and we're off like a rocket. Fortunately, I

had my boots wedged underneath a rail in the preferred manner, so I

wasn't left behind on the snow, but it was a close call.

The trip back was mercifully slower since we were towing a sled with

100kg of UPS and batteries on it.

Today's major task was to complete laying some cables from the AASTO to

the top of the Gtower. This is a major job, considering we have 10 reels

of multi-conductor cables, each about 30m long, with bulky mil-spec

connectors on each end. Even though we had a comfortably-wide 100-mm

diameter conduit, it took several hours, and a half-dozen attempts

before we found the right combination of cable attachments that would

allow us to pull all the cables without snagging. Kevin came up with the

winning combination of wrapping metal tape around the connector bundle.

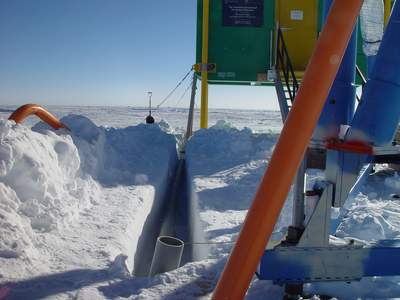

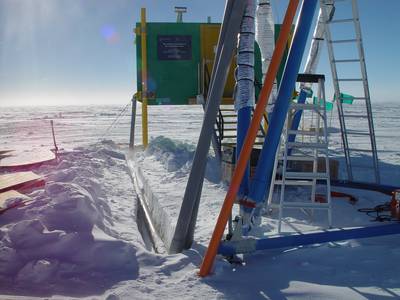

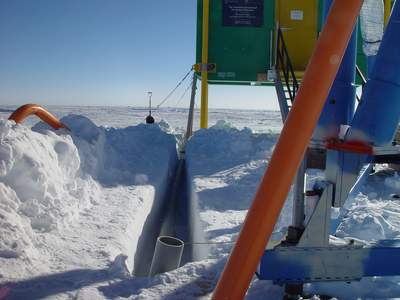

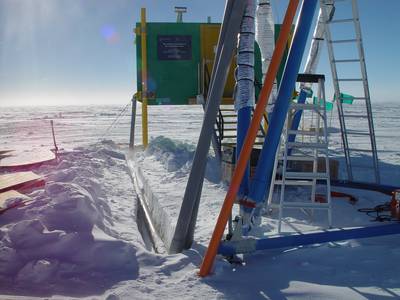

Here is the trench with three conduits layed. The AASTO is the green

and gold building, and you can see the nice staircase that the

carpenters made for us.

Some of the cables were wound in a roll, and some looped (the

difference is crucial if you want to avoid twists). Here is Kevin inside

the AASTO paying out all the various reels. I consolidated the cables

into a bundle before it left the AASTO.

Mark was immediately outside feeding the bundle into the conduit, and

Doug was up the tower pulling the cables through.

The stiff winds outside made it very difficult to do all the fiddly

jobs like tie knots in pieces of string. It wasn't until after dinner

that the job was complete.

On the way back from the AASTO, I recorded some video showing how one

enters the new station by going down into the Dome and then along

various tunnels. This clip

shows about half the journey - the second half involves some more

tunnels and then climbing up inside the "Beer Can" (visible in the first

few frames).

While I'm here at South Pole, my colleagues Jon Lawrence, Tony

Travouillon and Colin Bonner are hard at work at Dome C, at a latitude

of -75 degrees south on the Antarctic plateau. They are installing a

number of experiments, the most ambitious of which is the Multi-Aperture

Scintillation Sensor (MASS). I'm needed to answer questions on the

computer control system, and the delays in getting e-mails delivered

between Dome C and South Pole are quite frustrating (Dome C e-mails are

queued for daily transmission via Marisat; South Pole has intermittent

internet access, for about 12 hours a day).

25th of January 2004 - Gmount now working

There had been a couple of mysterious cylinders lying in the corridor

at the back of the kitchen, labeled "NASA/JPL Autonomous Vehicles Group"

(or similar). As I was walking past this morning, a "beaker" (scientist)

was trying to lug one of the cylinders down the stairs, so I gave him a

hand. It turns out that the tubes contained some sort of instrumented

balloon, that, I believe, is blown across the surface of the ice and

gathers data. I could be wrong about this, so don't quote me. Apparently

the experiment is called Tumbleweed.

Incidentally, as aluded to above, scientists in Antarctica are called

"beakers", and construction workers "gumbies".

Today the wind dropped to just a few knotts, which dramatically

improved the ease of working outside. Even though the temperature was

-27C, I had to take my jacket off to avoid overheating on the walk to

the Weatherhaven, where I met Mark, who was working hard on debugging

the Gmount. By chance I walked behind the instrument rack and noticed a

switch that appeared to be in the incorrect position. Mark confirmed

this, he then flicked the switch, and the Gmount came to life! We felt

greatly relieved, but a bit foolish. The altitude provides a good

excuse, the affect on slowing brain function is strongly noticeable.

At lunch I sat next to Scott, the station physician. Scott has just

wintered at Palmer Station (a remote US base on the coast of the

Antarctic Peninsula, with a population of around 18). He is now

wintering at South Pole, which will be an amazing experience. Given the

recent problems with the health of the station doctors (one had breast

cancer, one had gall bladder problems and a heart attack), Scott joked

that almost all of his internal organs were removed by Raytheon before

he was allowed down here.

After lunch, Mark and I helped out for a while in the kitchen cleaning

plates. This is an expected part of being down here, and with a station

population at close to an all-time record of 244 people, essential to

keep the kitchen staff sane.

A colleague of mine from UNSW, Paolo Calisse, wintered at the Pole

during 2003. It turns out that he inhabited room A1-204, which is right

next door to the one I am in now, so to bring back memories for him,

I've put together a short video

clip to show what it is like to walk from my room to the Dining Facility.

The clip starts with a view of the Dome from my window, and has lots of

shots of the Antarctic plateau taken through the panoramic windows of

the Dining Facility.

26th of January 2004 - Australia Day - lots of progress

Today was filled with all sorts of important jobs being completed. We

did a preliminary balance of the telescope and asked Bob Spotz to make

us a mounting bracket for the 20kg of lead weight that we needed. Mark

and I worked on an intermittent inductosyn problem with the Gmount, and

managed to see the fault on an oscilloscope. We swapped out a suspect

preamplifier module, but only time will tell if this was the problem.

Doug and Kevin routed the cables from their telescope through the

Gmount, and then worked with the Raytheon support folks to move a 70kg

control box to the top of the Gtower. The box was then powered up and

its temperature control system ensured that it maintained a safe

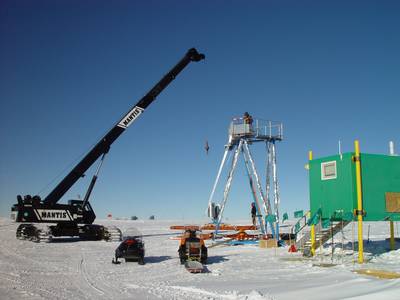

environment for the various computers inside. We booked the crane for

the telescope move on Wednesday afternoon.

Over dinner we had an interesting chat with Jon Emanuel, or "Cookie

Jon" as he is known. Jon is the Head Chef here at South Pole, and he is

responsible for all sorts of things, including ordering the year's

supply of food for the winter. It is truly amazing the quality of the

food that comes out of the kitchen here - a couple of nights ago we had

lobster, tonight we had blackened catfish. This last week we have been

particularly lucky with 3 incoming flights bringing "freshies", i.e.,

fresh perishable fruit and vegetables. We have had the most superb

quality avocados and tomatoes. These are amongst the things that the

winteroverers crave after a few months.

Here is Cookie Jon:

I also learned about Snickerdoodles (sp?) and gumbo. Snickerdoodles are

what Australian's would call a "biscuit". Their defining characteristic

is that they contain more sugar per unit volume than is theoretically

possible. "Gumbo" is something eaten in the deep south of the US; it

looks vaguely like a stew with offcuts of sausage and gristly bits. I

wasn't brave enough to try it, but many people did and they are still

alive.

Today was my shower day - we are allowed two 2-minute showers per week

(the rationing is due to the cost of melting the snow to make water).

Ahhh...feels good.

27th of January - the Gmount is moved to the tower

This morning we hear that the telescope move has been brought forward a

day, which suits us. It takes just half-an-hour to finalise the

telescope balance using the nifty bracket that Bob Spotz made. We then

wrap the 60m of Gmount cables, and prepare to leave the Weatherhaven.

Here is what it looks like inside the Weatherhaven tent where we have

been doing most of our work so far. Mark is in the background, Doug in

the foreground, and the Gmount is the blue thing in the middle with two

telescopes hanging off it.

At 11am a forklift turned up to move the Gmount out of the

Weatherhaven. The forks on the forklift can extend right into the tent.

It is a good day for the move, -28C and very low wind.

Here we are with the Gmount partially out of the tent.

And the Gmount was then transfered to a sled for its 1.5km journey to

the AASTO and Gtower.

An LC130 started its final approach just as we got to the skiway, so we

had to wait 10 minutes or so to cross.

Here is the the Gmount on the sled, being pulled by a tractor.

Over lunch I chatted with the scientist deploying the Tumbleweed

experiment - a 2m diameter ball that gets blown across the ice by the

wind. It was launched yesterday, and is already 50km away. It has a tiny

on-board computer which logs temperature, humidity, altitude, latitude,

longitude, and a few other things, and sends the results back via an

Iridium modem. The whole experiment is powered by lithium batteries. A

similar concept might be used one day to explore the surface of Mars.

Also at lunch time, a fifth member of our team, Jason, arrived. Jason

will be working on software.

At 2:30pm a mobile crane inched its way out from the station, and with

the expert work of the crane driver, and Dave and Sarah, the final lift

was completed in just 3 minutes.

Here is a video of the Gmount lift.

In the hour before dinner we wrestled with trying to assign IP numbers

to two APC MasterSwitches. Amundsen and Scott may have faced

numerous perils, but at least they didn't have to deal with recalcitrant

computers.

Fiona Thornewill's husband is also skiing to the Pole. He is taking a

slightly shorter route than she did, but left later in the season when

the temperature is colder, so he probably has a tougher job. Although,

then again, he is traveling with a group of skiers, whereas Fiona was by

herself. He is expected to arrive at South Pole within the next 24 hours.

28th of January 2004 - EES mounted, Gmount operational

Sleeping at the South Pole is quite difficult, for three reasons: the

sun doesn't set until March, the altitude makes for restless sleep until

you get acclimatised (which takes two weeks or so), and the extremely

low humidity plays havoc with your nose - making it difficult to breathe

easily, bloody-noses are common.

However, what really makes for difficult sleep is when the fire alarm

goes off at 2am. This is no ordinary fire alarm. Each room has a strobe

lamp and a loudspeaker. The lamp flashes so brightly that you are forced

to leave the room. The speaker is also very insistent. Fire is the

greatest danger we face here - in the dry conditions the station would

burn very quickly. And there isn't an abundance of water to help put

fires out.

Unfortunately, the new fire alarm system has teething problems and is

subject to numerous false alarms. So much so that it is basically

ignored by everyone except the fire teams, which is not a good thing.

After a satisfying breakfast of one egg over-easy on French toast, I

joined the rest of the team out at the AASTO. The carpenters arrived at

10am to construct a support for the External Equipment Shelter (EES) on

the Gtower. The EES is a heated enclosure containing CCD cameras and

computers that form the heart of the planet search experiment. The

carpenters have an amazing collection of DeWalt battery-powered tools.

Would you believe a battery powered circular saw? That actually works at

-30C? It's true.

At lunch time I finally met the elusive Jason, our fifth team member,

responsible for much of the instrument control software. Jason skied

between the new building and the AASTO.

After lunch, with the EES powered up, we attempted to communicate with

the computer in there. I wont bore you with the technical details, but

this took a couple of hours of concerted hacking. If we hadn't made

contact, we would have had to climb the tower and remove the computer

from the EES - a time-consuming and difficult job.

Fiona Thorewill's husband and a few others skied into South Pole after

lunch. They are currently camped about 50m from the Ceremonial Pole (the

barber pole with a sphere on top, surrounded by the flags of all the

Antarctic Treaty nations - it is about 100m from the actual South Pole),

and here is a close up of their tents. The black dots in the background

are skiway markers.

After dinner we complete the laying of the Gmount cables, and Kevin

hooked-up all 10 mil-spec connectors to the Gmount. Mark fired up the

software, and we all breathed a sigh of relief when the Gmount swung

into action.

29th of January 2004 - webcams; computer problems

Kevin flew back to McMurdo this morning. We will certainly miss his

enthusiasm, energy, and many skills. He is working on this project

pro-bono in his vacation time.

A twin-otter aircraft flew in, scooped up all the British skiers, and

flew off again. The actual -90S point about which the earth spins is

between the US flag and the sign on the right of the photo. I have been

told that in mid-winter the winteroverers occasionally go outside and

lie down near the pole and look up at the stars without goggles (if

there is no wind, this is possible for a short time even at temperatures

as low as -70C).

No sooner had the British skiers departed than another skier arrived -

a 64 year old gentleman, who, rumour has it, is the oldest person to

have skied from the coast to the Pole.

This morning I worked on upgrading our web camera, so you will soon be

able to see almost live pictures of the AASTO. In the afternoon we were

still having intermittent problems communicating with the computer in

the EES, so we decided to take a flat-screen monitor, keyboard, and

mouse up the tower and plug it in to the computer to diagnose it. This

was an interesting exercise at an ambient temperature of -31C. The

computer is randomly crashing, so we resigned ourselves to removing it

from the EES and working on it in the AASTO. We suspect a faulty memory

chip, but won't know until we conduct more tests.

Mark and Jason spent much of the day working on software.

Returning to my room just before dinner, I discovered that my "nurse

call" button was emitting a penetrating "BEEP" sound every 12 seconds.

Fortunately, a quick discussion with Scott, the physician, isolated the

problem to a new paging system in the Biomed area, and the beeping

stopped.

Today was the day that Biomed moved from its old quarters under the

dome to its final location in new building. The new facilities are

nothing short of amazing. There is a nicely equipped operating

theatre, prompting a joke with Molly, the summer physician, about

conducting alien autopsies...

Speaking of aliens, here is a picture taken (not by me) in one of the

numerous underground tunnels at South Pole:

The temperature in these tunnels is about -57C, which is the average

annual temperature at the South Pole.

At 8:30pm the cooks held a thank-you supper for the people who had

helped out in the kitchen over summer. There were some excellent

cheeses, salmon, three bottles of very nice red wine, and a spectacular

almond/coffee ice cream desert. It was a very pleasant way to end the

day.

30th of January 2004 - more computer problems

With the computer removed from the EES, we were able to run some

extensive memory diagnostics, and the machine passed with flying

colours. We began to suspect the solid-state hard disk, and, sure

enough, after leaving the disk outside for 20 minutes at -30C, it showed

intermittent operation until it warmed up to closer to 0C. This disk has

an operating temperature range of -40 to +85C, so it is clearly out of

specification - fortunately we can control the temperature of the EES,

so if we set it to +10C we should have a reasonable margin of safety. We

also have a backup disk (of the spinning variety, not solid state). We

normally try to avoid spinning disks since the altitude of the Pole

causes them to fail at a higher rate than at sea level.

It took some hours for us to repair damaged files on the solid-state

disk, and to have the computer working again.

Both Jason and Doug are now skiing between the station and the AASTO.

It is only marginally faster than walking, but it looks like good fun.

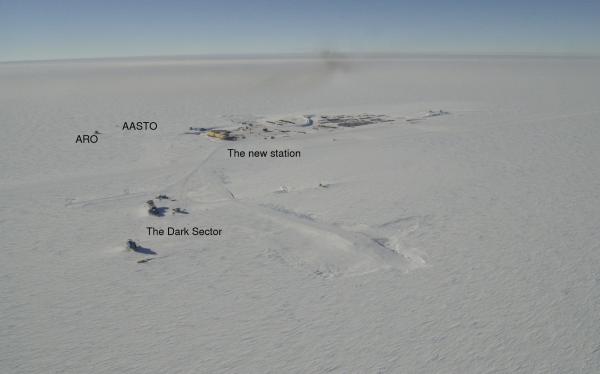

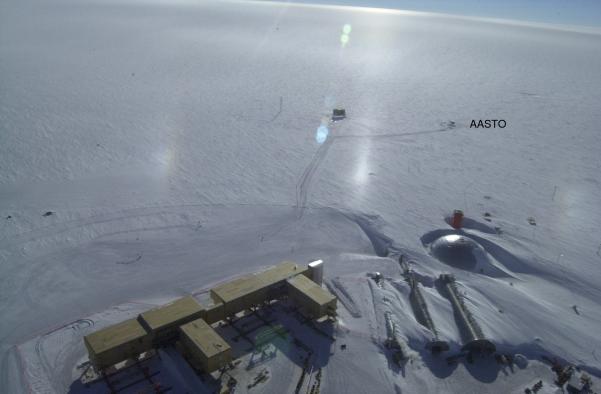

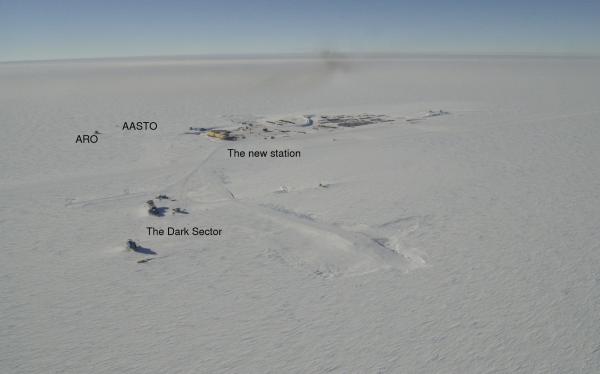

An LC-130 did five passes of the station taking aerial photos. Here is

a view of the entire station:

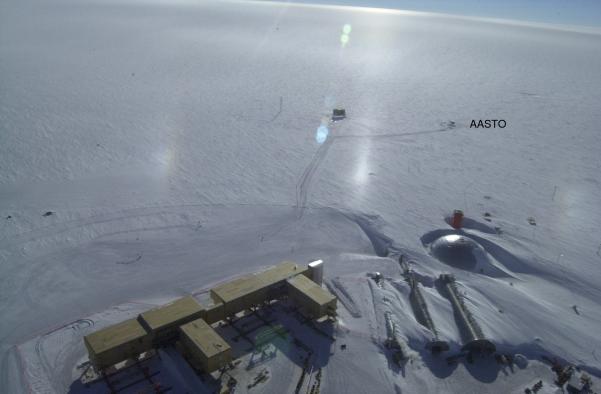

Here is another view showing the AASTO, with the new elevated

station in the bottom left, and the dome in the middle right.

And here are some of the telescopes in the Dark Sector (where most of

the astronomy is done).

The dish-shaped object on the left is Viper, and the one on the right

is DASI. The Weatherhaven is the blue building on the far right.

In the afternoon Mark organised some "retro" cargo to send back to

Australia, and worked on the Gmount software.

The highlight of the day was that I got to have a shower, my first one

in 6 days. The showers have been off-line this week due to water

restrictions after some sort of problem with the power plant. We get our

water from a Rodriguez well (or "Rod well"), which is a underground

"bulb" of water formed in the ice by dumping excess heat from the diesel

engines in the power plant. The heat is sufficient to cause a roughly

spherical volume of water to remain liquid, even though the edges are in

contact with the ice. An interesting side effect of this is that

micrometeorites that have been suspended in the ice for perhaps

thousands of years fall to the bottom of the well, where a research team

uses a robotic "vacuum cleaner" device to scoop them up for study.

30th of January 2004 - telescope calibration

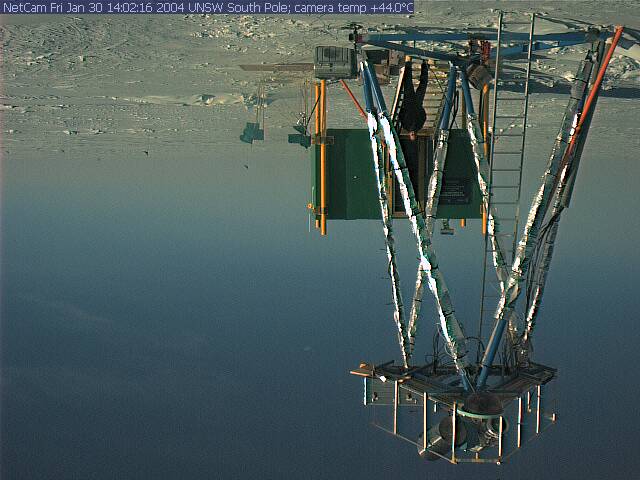

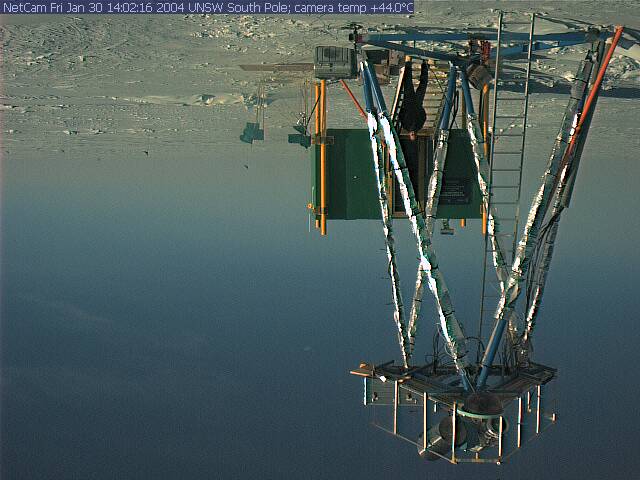

I completed the installation of the web camera that views the AASTO and

the tower, but the image is upside down! This is kind-of appropriate for

the South Pole... it is also a good illustration of how effective

gravity is! That's me in black on the AASTO stairs.

A good fraction of the day was taken up installing electrical switches

on the computer that lives in the EES. The switches allow us to easily

swap between using a normal spinning hard-disk, and the solid-state

flash disk. Without the switches it would be a multi-hour operation for

the winteroverer scientist to make the swap (which may become necessary

due to the failure of one or other drive). We also attached a carry

handle to the computer to enable it to be quickly and safely lowered

from the tower with a rope. We need to think about these

ease-of-maintenance issues, since climbing the tower in winter, in the

dark, at a temperature as low as -70C, would be a formidable challenge.

Incidentally, our winteroverer is Dana Hrubes, and our experiment is

one of 11 that he is looking after this year. Dana has an interesting

history - his background is aerospace engineering and rocket motors,

including working on the Galileo probe for the Jet Propulsion

Laboratory. He also takes superb photographs.

In the afternoon I spent some time on the tower leveling the Gmount,

which needs to be done to a precision of about 1 arcminute (1/30th the

diameter of the Sun). Mark then performed an initial calibration of the

mount by pointing at the Sun (with appropriate covers over both our

telescopes!). Since it was fairly overcast, we then pointed at the

nearby ARO building and attempted to take an image of it with the

planet-search telescope. We soon discovered that the focus motor wasn't

working, which was easily fixed by moving a cable in the EES. But then

the shutter refused to work...at which point is was 10pm and we were all

too tired to continue. The multiple journeys up and down the tower had

taken their toll on my energy. The windchill temperature was -53C, and

three layers of clothing were necessary.

Here is an example image from the pan-tilt-zoom web camera on the

tower, it shows the new elevated station at quite high magnification:

and here is a wide-angle black-and-white camera that looks up at the

telescopes. This is useful for debugging purposes during the winter. It

has an infrared illuminator so that we can see the telescopes in the

dark.

1st of February 2004 - telescope focused

A reboot of the computer resolved the shutter problem from last night.

We were then able to focus the telescope on the ARO building. Here is

our best image, with Mark Jarnyk visible walking to the AASTO. The

vignetting at the edges of the image is due to the shutter transit time

during the 20ms exposure.

We then tried to take an image of a bright star, but this was

unsuccessful, due to thin cloud.

We have some concerns about the temperature of the solid-state disk in

the EES, and we need to explore the option of adding some additional

heaters.

For fun, I took a video of myself

climbing the Gtower. The background noise that you hear is the wind,

which was about 15 knotts at the time. When one of us is climbing the

tower, we always have at least one person in the AASTO occasionally

checking on us. Once after coming down from the tower I lay face-down

spread-eagled in the snow for a joke, but when no one noticed after five

minutes I brushed myself off and came back inside.

In the evening Doug gave an excellent talk about the planet search

experiment as part of the weekly Science Talk session. About 40 people

turned up, which is about 1/5 of the station's current population.

2nd of February 2004 - frustrating wait for clear weather

This morning we decided to "bite the bullet" and bring the computer

down from the EES yet again, this time to install an additional heater

near the solid-state disk. When we opened up the EES we noticed that a

considerable quantity of snow had managed to sneak in - this is a

characteristic of "diamond dust", the tiny particles of ice that fall

out of the sky and are blown by the wind. Diamond dust can penetrate the

tiniest crack in your equipment. We did our best to seal up an area near

some cables where the ice had probably found its way in.

Here is a video that shows a

particularly strong display of diamond dust in the air. The

particles look quite large in the video, which is simply a result of

most of them being out of focus. To the eye they appear as microscopic

glints of light. This is how snow falls at the Pole - we never see any

snowflakes (although see the entry for 6 February).

The sky, while mostly clear, had sufficient thin cloud to prevent us

from seeing stars today. So I spent the afternoon working on software.

My colleagues at Dome C tell me that it is clear there.

At 8:30pm we were treated to the showing of a documentary made by Tom

Pi, one of the carpenters. Tom has a good eye for a camera angle, and

has produced an excellent hour-long video covering many aspects of

station life over the 2003-4 summer, including interviews with a number

of people.

3rd of February 2004 - set the controls for the heart of the sun

Today was mainly spent doing a few odd jobs: tiding up the AASTO,

turning the web camera the right way up, and securing cables to the web

camera and on the Gtower.

Once again, light cloud prevented us from finding a star.

However, not to be deterred, we decided to observe the Sun instead. A

quick calculation showed that we needed to reduce the aperture of our

telescope from 200mm to less than 1mm. So, we drilled a tiny hole in a

sheet of aluminium and placed it in front of the telescope with a whole

bunch of filters for good measure. Mark instructed the Gmount to point

at the Sun (normally it objects strenuously to this, and goes out of its

way to avoid getting close to the Sun even when moving between other

objects). Jason then took an exposure, and there was the Sun, within 0.5

degree of where we had guessed. So at least this confirmed that our

preliminary alignment of the Gmount was correct. Mark updated the

parameter files to centre the Sun, and after dinner checked that the Sun

was still centred. This verified the level of the mount, so that we are

now close to being set for a winter of observations.

At 8pm most of the males at the station (we're about 50-50

males/females) assembled in the dining facility to watch the 38th

Superbowl. The game was actually played in the US on Sunday, but the

video tape only made it to the Pole today. It is a long tradition at the

Pole to deliberately shut-out all news of which team won the game so

that the video doesn't loose its excitement. American football is a

decidedly unusual game - I didn't see the ball once during the first

quarter, there were just a bunch of huge guys in tight trousers running

in random directions and crashing into each other. And lots of

shots of various coaches chewing gum/tobacco and speaking into Motorola

headsets. The highlight of the game seemed to be during the half-time

entertainment when Janet Jackson's right breast was exposed for 2

seconds at the end of a song - apparently this has resulted in a $20

million lawsuit and MTV loosing the rights to host the entertainment.

The kitchen staff came to the party with appetizers and Jon produced a

whole smoked pig.

STOP PRESS: Towards the end of the Superbowl, the sky cleared perfectly

and we saw the bright stars Canopus and Alpha Centauri through the

telescope in broad daylight.

Here are Doug, Mark and I in the AASTO looking pleased with ourselves a

few minutes after the first detection. I won't show you an image of the

star, since it is blurry (due to the 3 filters we have in front of the

telescope to reduce the sky brightness) and almost undetectable unless

you blink rapidly between two image taken at slightly different

telescope positions.

4th of February 2004 - software and more software; Dome C panic

After the excitement of seeing stars last night, we awoke this morning

to strong winds (21 knotts), but relatively warm temperatures (-28C) for

this time of year. The wind really makes it unpleasant outside - the

windchill temperature was below -60C. The wind also creates some

interesting effects as it blows the particles of "diamond dust" across

the surface. It looks rather like smoke flowing across the landscape,

just millimetres above the surface. I took a video to show the effect, and

another looking at snow blowing past

one of my boots (you need to be hard-core snow enthusiasts to find

these videos interesting). The snow at the Pole move somewhat like very

fine grains of sand. If you pick it up in your gloves it just trickles

over the edges. You can't make a snowball by clumping it together with

your hands, since there is no liquid water to help the snow stick.

We have acquired a US and Australian flag for the AASTO from Paul

Sullivan, the Science Support Manager here at South Pole. Doug and I

spend half-an-hour installing the flags on the AASTO. We do this every

year, primarily for the web camera, and the flags mysteriously vanish

before next summer. I understand there is a brisk trade in flags that

have been flown at the South Pole.

Mark is leaving for McMurdo tomorrow, so he spent a couple of hours

instructing Doug and Dana on the intricacies of the Gmount software.

I should mention that Jason has been working long hours on the Vulcan-S

software. He was in the dining facility working on his laptop when I

went to bed last night, and he was still there when I woke up the next

morning. He is happy with his progress. The entire experiment, like all

of the AASTO and AASTINO experiments, is automated and can be controlled

remotely.

At 9:30pm there was an all-call: "Michael Ashley please phone COMMS on

282". It was a message from Jon Lawrence at Dome C to call him

back. So I used the Iridium satellite phone in COMMS to call Jon.

It turned out that while he was originally scheduled to fly out on Feb

8, he had just been informed that he had to leave tomorrow morning at

6am! Jon still had a long list of jobs to work through to ensure the

AASTINO was ready for the winter, so he was in a state of mild panic. I

also panicked when I realised that one crucial piece of the software,

the piece that allows us to control the AASTINO from the Internet, had

not been fully installed. Without this software the AASTINO would sit

there doing nothing all year. Fortunately, the internet connection to

South Pole was up, and with some rapid e-mailing, downloading, and three

15-minute Iridium phone calls, we had the software in place and tested

by 1am.

That's me on the left in COMMS (in the Dome) talking to Jon on the

Iridium phone; a COMMS operator is on the right. COMMS is open 24

hours-a-day and handles all the radio traffic, aircraft movements,

emergency coordination, and just about anything else you can think of.

and here is a distant view of the Marisat antenna which is the main

source of Internet connectivity at the Pole. Note that the antenna is

pointed just above the horizon, this is because it is tracking a

satellite that has been boosted slightly out of geostationary orbit (a

truly geostationary orbit is below the horizon from the Pole).

Some hours later, Jon was able to convince the station manager to give

him 2 more days, so our state of panic has been alleviated. Dome C

closes completely on Feb 9 (unlike South Pole which is occupied all

year), leaving our AASTINO to fend for itself until next summer. You can

track its progress at http://www.phys.unsw.edu.au/~mcba/aastino.

Colin will still be flying out early, to join Tony who is already on

the coast surrounded by penguins waiting for the l'Astrolabe ship to

take him back to Hobart.

Incidentally, you can read Tony's excellent and amusing diary entries

from Dome C by following the links at http://www.phys.unsw.edu.au/astro.

Diaries from John Storey, and Jessica Dempsey from this season are

there too, plus historical diaries going back a decade.

5th of February 2004 - final jobs

This is my last full day at the Pole. Mark left this morning. Doug and

Jason are staying over the weekend to finalise their software and to

perform last-minute tests.

Out near the AASTO there are all sorts of underground vaults where

various seismic and other experiments take place. I heard the story

today that Dana visited one of the vaults that hadn't been used for 15

years. He went down the ladder into the dark tunnel under the ice, and

found a door. On the other side of the door was a small office with a

desk, the light was on and the room was heated! It must have been this

way for 15 years. Fortunately there wasn't a skeleton sitting on the

chair with a note: "door jammed Feb 5, 1989, giving up hope of rescue".

Here is an example of an entrance to an underground vault. It is about

100m from the AASTO, and apparently contains a magnetometer.

Doug and I ski-dooed out to the AASTO with a sled to bring back the

trash (cardboard boxes, etc) for sorting into various categories. The

ski-doo was a sleek new version with electric starter motor and other

comforts - Kevin would be green with envy. The maximum speed on the dial

was 130 mph. This time I took a video of the ride. The 3m 48s of

nail-biting, adrenalin-pumping, action comes in two formats, a low resolution 1.5MB version suitable

for a modem, or an 11MB version if you

have plenty of bandwidth. My apologies in advance for all the

"yee-hahs"...

After "bag drag" at 7pm, I hiked the kilometre out to the Antanov, a

single engine aircraft that a group of Russians flew to the Pole three

years ago. When they arrived, their fuel turned to gel due to the cold,

and they had to leave the aircraft behind. Rumour has it that they will

attempt to fly it out one day.

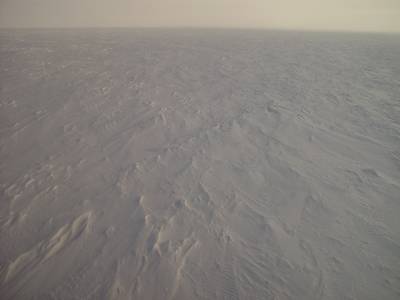

Here is the view from the ARO building looking away from the station.

Not much there.

At 9pm I checked in with Jon at Dome C via Iridium phone. Everything is

now on-track - the AASTINO is controllable from UNSW, and Jon has

another two days to finish his remaining tasks. Jon is one of only

12 people now left at Dome C.

6th of February 2004 - leaving for home

After some last minute e-mails and software jobs, at 11:10am it was

time to board the LC130 for the trip to McMurdo. I said my

goodbyes to Doug and Jason, who will be staying another few days,

largely to wrap up software control issues.

While we waited for the LC130 to be refueled, it actually started to

snow! This is a rare occurence at the Pole, where most "precipitation"

is in the form of wind-blown ice-crystals ("diamond dust"). The snow

only lasted for 10 minutes or so.

We had a "straight-through" flight, which meant we had a brief stop at

Williams Field (near McMurdo, on the Ross Sea ice shelf) to change

planes before heading to Christchurch.

The photo shows us about halfway between the Pole and the coast. Our

carry-on bags are stored in the middle, making a comfortable spot to

rest our boots on. After takeoff the aircraft is pressurised to an

altitude lower than the Pole (you can tell, because water bottles with

air in them become compressed).

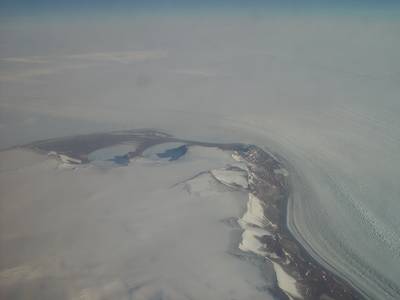

After about an hour after leaving the Pole we flew over the spectacular

Transantarctic mountains and the Beardsmore Glacier. The scenery is

absolutely awe-inspiring. The photos below do not to justice to the

spectacular views that changed every few minutes. On a previous trip to

Antarctica we flew just 100m above the Beardsmore for its entire

(200km?) length. That was truly an experience of a lifetime.

Here you can see a glacier (the Beardsmore?) turning a corner around a

mountain range.

Here is a typical view of snow-draped mountains. This vast wilderness

is completely untracked by humans. There is evidence of crevasses.

A small glacier pouring over a pass between mountains. This is how the

high Antarctic plateau gradually makes the transition to sea level.

Upon arrival at McMurdo we were hearded into the passenger compartment

of a "Delta" for the 30-minute ride to the Pegasus ice runway. The Delta

was capably driven by Heather in the cab up front, who thoughtfully

gave us a UHF radio so that we could communicate with her if we

needed to. Heather explained that the journey could be a bit rough, and

that if she hit a bump we could find ourselves hitting the roof. There

were supposed to be seatbelts somewhere, but they were too difficult to

find. It would have been a good lark at the end of the trip for us all

to assume upside down and skew positions on the floor so that when

Heather opened the back she would get a surprise. I wasn't sure how the

15 construction workers on the Delta with me would like this idea, so I

kept quiet.

We then spent a hour being loaded like sardines into a C141, and after

interminable delays, finally took off for Christchurch at 5pm.

The trip north was absolutely miserable. 132 "PAX" with no room to

move, squashed together as close as possible on webbing seats in four

rows of 33 people, with knees touching the adjacent row. The temperature

hit over 30C two hours into the flight. With thermal underwear, ECW,

and bunny boots, it was a nightmare. This is really the only negative

part of the Antarctic experience - it is particularly irritating since

it is so unnecessary. Simply turning down the temperature to 10C would

have made the trip bearable, but for some unfathomable reason the

aircrews rarely do this. The Airbus 320 that took me from Sydney to

Christchurch could hold 180 passengers, and was smaller, faster, more

fuel-efficient, far less noisy, and much more comfortable.

The blue curtain in the photo below surrounded the men's toilet (a drum

with a funnel). To clamber to it from half-way down an aisle was quite a

challenge. Some people waded through the sea of legs, others balanced

precariously on a metal bar about 1.5m off the floor (obscured by the

curtain in the photo) that separated the two sets of aisles.

At 10:15pm we arrived in Christchurch, and after a mercifully quick

trip through customs we returned our ECW and dispersed to various hotels

throughout the city. Christchurch was warm, humid, and at sea level.

Bliss. The next day it rained lightly, which is something that the

winteroverers really miss during the year at Pole.

A quick e-mail check showed that Doug and Jason were making rapid

progress on the remaining software issues. Hopefully we will have some

planet discoveries to tell you about during the year!

Until next time,

Michael